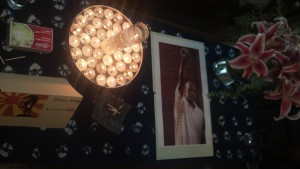

Brian Anders, in memoriam

I wrote this shortly after Brian passed away, which was a year ago today. Decided to post it after a celebration of his memory last weekend, on Ontario Road in Adams Morgan. We planted a tree among his ashes. R.I.P. friend.

I’d only met Brian Anders a few times, and each time I’d only spoken with him for a few minutes max, but it didn’t take much more than that to turn him out to a meeting that ran through almost an entire spring Saturday. Turns out this was one of Brian Anders’ natural habitats.

Brian arrived even before the Save Our Safety Net campaign’s strategy session began, and he stayed well past the official end. We were meeting at Bread for the City’s Northwest center, and it was the middle of our campaign. On the agenda: planning a series of direct actions that would pressure City Council to raise taxes instead of cutting social service budgets. i

Among the crew assembled at this meeting, Brian was nearly unique: he actually looked like he fit the part of the kind of person who might actually receive help from the safety net—a bald black elder breaking bread with a group that was almost entirely white and trim and under thirty. The truth was, only one or two other people in the room had more than a decade of time in DC under our belts; most had only one or two years. We were so conscious of that, and we wanted to change it, so we’d put the call out far and wide… Brian was the one who showed up.

I never heard Brian even acknowledge this point. He’d simply been around the block a lot of times, and if anything, he made you feel like you’d been there right along with him. When we went around the table sharing stories about our experience with direct action, Brian mentioned his experience with the Community for Creative Non-Violence so casually that I think it might not have made an impression on many at the table. For me, it was like a missing plank on the bridge we were trying to build had just fallen into place.

In the months before we’d launched SOS, I’d read up a fair amount of history of DC’s social movements, once great and now all but forgotten. CCNV was the fierce locus of a radical powerful movement in the late 70s and 80s. The story I had been told was that a flood of anti-war activists had come to DC in the 60s, and in the wake of the war and the riots they decided to stick around, in the midst of the rubble, so the story goes, which lay across the city festering like an open wound. (It wasn’t until later still that I would read about the veins of the black power movement that coursed here and eventually flickered out on what seemed like a totally different trajectory from the radical mostly-white activists of CCNV.) CCNV activists actually engaged with the extreme poverty in the city — organizing shelters, procuring food, pro bono lawyers and medical care — and as they served they also learned together, eventually honing a practice of direct actions and mass civil disobedience. Along the way, CCNV took on not just District mayors but United States presidents—at one point, they even occupied a building just blocks from the White House, turned it into a shelter and called out Reagan for the poverty sprawling right in front of his window. CCNV called the public on its responsibility to address inequality, and they commanded an audience. ii

Today, CCNV is another homeless shelter, and it has hardly any kind of public presence other than a reputation for mismanagement.

For months, I’d poked around town to see who was still here from the CCNV era, who was still working, organizing, anyone who might be willing to talk. I’d found just one guy. He used to organize in homeless shelters as well, and he seemed to know a lot—but he was scarred, and cynical. Bouncing from one non-profit management job to the next. The guy told me lots of stories about Mitch Snyder, the lightning rod of a ringleader of the CCNV movement. Snyder had Americanized the act of the hunger strike, and caught a tremendous amount of attention for it, and then a diminishing amount, and then he hung himself in 1990. Snyder’s wife is still here, this guy told me, but she won’t talk to you, or anyone, about any of it. And that was about it about that.

A few of the senior staff at Bread for the City seemed to have a distant memory of the CCNV era—the desk staff who’d been here almost from the beginning would laugh about how they used to march out of work and right down to City Hall. The managers who’d been here almost twenty years would just shake their heads at the thought. There had been two kinds of approaches to poverty in those days—do what you could to help those who were suffering, and wield the truth like a righteous cudgel—and for a while there they’d been entwined, with electric polarity, but eventually they got pulled apart and guess which one held out.

And well so here we were again, planning our actions to save DC’s safety net, and now Brian was telling us about how CCNV used to do it. In the course of a tense meeting (just how direct would these actions be, anyway?) Brian cracked wise and soothed our nerves, which were raw from over-analysis and inexperience. He cracked jokes about Councilmembers, and he displayed an acute knowledge of the geography and security apparatus of the John A Wilson Building, where almost all of the actions would take place.

When it came time to commit to next steps, Brian personally guaranteed to turn out 20 people, a number that only I was cocky enough to match.

In the final go-round of the day, each member of the assembled SOS crew shared our vision for the future. As cliche as it sounds, Brian’s words took my breath away.

“I see something here. And I’ve seen a lot of things, but I think this can be big. I think a lot people out there are waiting for exactly this. They’re ready for it. They’re hungry, and I don’t just mean for food. People are hungry for the call to rise up against this deadening corporate state and the systematic disenfranchisement of everyone who isn’t a wealthy elite. The time has come to take a stand. I think I see here the spark that we’ve been waiting to see for a long time. And I think that what we do here is not just going to shake things up here in DC; I think it’s going to ripple across the country.”

Well. A couple hundred people turned up for our actions, some of the highest numbers most anyone had seen in the Wilson Building for years.iii And eventually, probably partially because of Save Our Safety Net, City Council did increase taxes on high-income earners in DC.iv

In the years after SOS, even as I stepped back from direct actions and budget advocacy in general, I kept in contact with Brian whenever possible. If I needed to know who to talk to, Brian had contacts. If I was stuck, Brian had ideas. When I was anxious and not sleeping well, Brian advised me on how to clear my head, to meditate, and have some fun. I can’t say it always worked; I still find all of those things to be pretty hard. But this did not diminish my gratefulness to hear it from someone who’d been doing this for years, from someone who said, I see you, and I know it’s hard, and it’s going to be okay.

But when I first learned about his cancer, I hadn’t seen Brian for quite some time. Not since the peak of the Occupy encampment, which I only visited two or three times. Each time he’d been in the midst of it, busy, a fervent liaison between the camp’s activist core and the growing number of homeless people who had settled in to the site.

Maybe he looked a little thin, and I certainly noticed that he seemed tired. But it was only through his posts on Facebook that I learned about the cancer.

I sent him a message of well wishes, but otherwise just watched the feed, in distracted fragments, as his prognosis seemed to worsen. Not only was he ailing, but it seemed like the hospital was trying to turn him out early, without proper care. He was defiant, asserting his right to care – but it didn’t sound like a winning fight. Then his updates stopped for a while. When I saw him eventually re-emerge, with a smattering of indignant lefty links and vintage funk via Youtube, I felt genuine relief. Brian had landed in Joseph’s House, the last remaining free hospice in the city, a serene and humane place, one of the only places I knew he’d be taken care of.

I went to Joseph’s House less than a day left before my travels began. Brian was lying in bed, reading. The room had that hospital smell, which has always reduced me to near uselessness. Brian was so thin. I recalled seeing Ted Pringle, Bread for the City’s food program director, in the weeks before pancreatic cancer took him from Bread and the world; it was shocking, but Ted had been a big robust man. Brian had always looked weathered, gaunt and snaggletoothed—but also tough. A wiry fighter. Now his body was barely there.

His eyes still alit fiercely though. Jesus, I thought, he looked like fucking Gandhi.

As I walked in, he looked up from writing in a journal on a tray in his lap. He offered me a seat. Within just a moment we were talking shop.

The last time we’d talked had been before I’d left Bread for the City, so I caught him up on my whole story: too many risks taken, too many limbs gone out on, a few envelopes pushed too far. Pushed out. Alone. He nodded, and even laughed. Brian knew as well as anyone what a community organization is and isn’t capable of. He told me he’d been surprised to see all that we’d gotten up to there in the first place.

“But don’t second guess yourself,” he said. “This is just how things turn out sometimes, they take a turn you didn’t expect. We just keep on pushing forward. And you are not alone,” emphasizing the two words. “You know that.”

I nodded. But my reply was full of doubt. The bright vision shared by those of us who’d started SOS just three years ago was now a tattered rag. Like the story of CCNV—with pitifully smaller stakes and a much quicker arc. For the first time since I’d begun intentionally organizing, I couldn’t see the path forward. I wasn’t even sure what direction forward was any more. I told him all this.

“Well, I’ll tell ya,” Brian said, his eyes beaming, “I would trade places with you in a heartbeat.”

I felt immediate hot shame at being so self-centered and pitying, and stammered out an apology. Brian waved it off.

“I’m excited for you,” he said. “Because you don’t know what the heck to do. But I can tell you’re still going to do something anyway. And that’s a powerful place to be.”

I…

Well, I changed the subject.

We talked about Joseph’s House. Brian praised them for a stretch of minutes, pausing only to point out how many more people need this kind of care right at this very moment.

“Now that I’m here, I can finally focus on getting out.”

That wasn’t my understanding of what happened here at Joseph’s House. But I nodded.

“I’m really focused now. I’ve been keeping a journal…” He reached over and grabbed a notebook, to hand to me. I flipped through it; detailed notes of sleep patterns and bowel movements alongside rhetorical questions about spirit and dignity, and proclamations of the universality of human rights.

“I feel like I have a new purpose,” Brian said as I skimmed the entries. “When I get out of here, I’m going to focus all of my energy on advocating for health care reform. The way this system dehumanizes people, just puts you in the grinder right when you’re at your most vulnerable…” His fists and jaw clenched for a moment, and then suddenly softened as his eyes looked out the window.

“Now though I’m focusing on the positive. Thinking positively. Positive energy.” He closed his eyes; settled into the bed for a minute, clearly a practice that he had agreed to undertake. It was working; he was at least for that moment, fully himself. And he told me he was “fired up and ready to go.”

In that moment I believed him. Despite the gauntness and the smell of that room, Brian was right there, still fighting and waiting and planning and believing.

I couldn’t resist switching back into organizer mode: “Have you been involved with any video?” Brian misunderstood, and thought I was asking for a referral for my own project.

“Video? If someone needs video, you should talk to Liane, her Grassroots Media Project can help you…”

Both of us, still organizing.

“No, Brian, I mean video of you. We need to share your stories. We need to have them for keeps, you know?”

“Oh, yeah. Well I’ve been writing a lot… but no, haven’t done any videos. That would be fun, though!” He grinned, not as widely as he used to.

I told him I’d ask around, see if we could set up a little documentary session. (I did send some emails, found some people who were thinking the same thing – we talked about meeting up upon my return, but Brian would already be gone by then. I don’t know if anyone ever did sit with him and a camera after all…)

Brian and I bade each other farewell, godspeed and good luck, and see you soon.v

I learned so much more about Brian Anders in the weeks after he died, in the memories circling around our little corner of Facebook and the smattering of obituaries. He was a Vietnam veteran, and had struggled for long with PTSD before having his own political awakening and choosing this work, for life. His CV went far beyond CCNV. It seemed as if half the homeless men in the city had been helped at one point or another by Brian himself.

The wake was at Joseph’s House and it was packed past the door with people old and young, come to pay their respects. Here was so much of the deep experience that, years before, I’d searched for without success. And so many of my peers who had also been mentored by the man.

We took turns sharing stories. Within the grief, hot anger shone through:

“Brian’s cancer was totally treatable,” said one woman, “and here he was, a victim of this inhumane system that he fought all his life. It denied him the care that could have saved him.” Another, between sobs: “It makes me so angry, to have seen so many of our black men suffer this fate.”

As I contemplated what I should say, if anything, I thought about that one other veteran of CCNV, with whom I had sat down to speak years ago, before meeting Brian. That tired, sad man. In the same conversation, he had alternated between trying to recruit me to be his partner, and discourage me from trying to change anything at all.

When I stood up I talked a bit about how I knew Brian and then found myself recalling this conversation with that other guy: “‘This city will kill you,’ he told me. He was trying to warn me against getting in over my head. Well, what I want to say here is that Brian was the opposite of that guy. Brian was right still ready to rail on there in his fucking death bed, unwavering, ready to get back out there and go to work. His spirit was totally alive even then, and I can feel it still here in this room.”

There were so many people in Joseph’s House that we couldn’t all see each other, so we listened carefully. When the last story had been told, we all stood and sang “Lean on Me,” and as I wept, a sister religious reached for my hand and took it, and I thought about how sorry I was that I didn’t try harder to get a video camera there in his last days. I could have sent more emails, even made a fucking phone call, anything to get some greater record of this man who was finally betrayed by a system he’d tried to save for itself all his life. Yet another person I hadn’t known how to help. With shame, I recalled that alongside the mad respect and love, I also felt pity for Brian, a specially sickening kind of sadness, to realize that I didn’t really even feel that populist hope which still animated him until the end; my gut grumbling that the revolutionaries and the reformers alike carry on with exhausted logics, their myths creaking into tragic irrelevance. Even if I’d shared my disbelief with Brian, I don’t think he would have argued with me, or even taken offense; in fact I believe I’d’ve learned a thing or three just by talking with him about it. But I held back, and now there’s only the memory of his stories, of a past where it all seemed possible. I’m sorry, Brian. I am still going to fight, maybe not at the meetings and the actions and in the streets with all the people, but there are many ways to fight, and I believe we can see it, the dawn of the new world that you always believed was just a rally away, and I’m thankful for my chance to search for it alongside you even for just a few moments.

28. August 2013 by greg.bloom@gmail.com

Categories: DC, Stories |

Tags: organizizing |

Leave a comment