Something is not necessarily better than nothing: Introducing the Principles of Equitable Disaster Response

Last week, a distributed team of community organizers published the Principles of Equitable and Effective Disaster Response. This is a document that we’ve developed through a series of in-person convenings and distributed rounds of feedback over the past two years. (You can review and comment upon the original draft here.)

We first articulated these principles with natural disasters in mind, but now – with a pandemic emergency upon us – we’re sharing them in hopes that they may be useful for people and communities that are mobilizing to respond to this new global crisis.

Below I’ll share some backstory on how I came to be involved in producing this document, and why I think it matters.

Hard Lessons from Hurricane Irma

During the week before Hurricane Irma in 2017, I started up the Irma Response slack which quickly grew into a virtual network of about a thousand ‘digital crisis responders.’ As a network, we did some things that I’m proud of.

In the end, the storm swerved past Miami-Dade. The disaster never quite happened (to us, anyway). Nevertheless, this experience was sobering for me.

First and foremost, I saw firsthand how our institutional systems were almost universally ill-prepared to respond to this crisis. From governments to nonprofits, it was bleak: poor plans, poorly coordinated and poorly communicated. (The number of shelters were woefully insufficient; the evacuation order came late and left tens of thousands jammed on roads as the hurricane approached; the government and the Red Cross blamed each other. I never did find out what the Florida VOAD — Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster — was supposed to be doing, let alone what it actually did. Etc.)

I also saw how readily regular people from all over the country and the world rallied to help online. This swarm of support was initially exhilarating, then eventually exhausting and frustrating. I saw alarming gaps between these digital responders’ good intentions, their ideas, and the reality of what people needed on the ground.

Most importantly, I saw how the most urgent and appropriate responses to the situation came directly from communities that were most vulnerable to this crisis. Local leaders like Vee Gunder were the first to respond in the communities, with the clearest line of sight to what was needed, and the strongest connection to the people in need — and they would still be there working after the attention withered away. Amid all the attention paid to either the mistakes of the formal institutions, and to the flashy websites and data visualizations produced by the network of civic hackers, these voices were the most important — yet the hardest to hear.

The Crises of Network-Centric Crisis Response

Since I started the Irma Response network, I felt some responsibility for the things happening in it.

In the week before the storm was projected to hit, I found myself spending 18+ hour days tending to the network. An enervating portion of that time entailed responding to crises that were precipitated by our own crisis responses. I intervened when I found people putting out information that could put vulnerable Florida residents (like undocumented residents or disabled people) in danger. I interjected when I found people hacking on “first thought best thought” applications that — if they’d ever be used at all — would waste a lot of time and energy, and maybe even make a messy situation worse. I spent hours a day asking why people were doing various things, and asking people to reconsider whether those things really ought to be done.

The most common response I got was: “well we have to do something!” And I’d have to point out that this was not actually true.

These were difficult conversations. Everyone involved had the best of intentions. They were volunteering their time, out of care for people in danger. They did not feel like there was time to waste in “philosophical discussions,” and they did not feel like we should be “political.”

And at a glance one could understand where they were coming from: with no money and a matter of days, our network built websites, and generated data visualizations, that looked way better than those produced by government agencies and giant organizations with multi-million dollar budgets and timescales of years. Our digital products loaded faster. They were ‘user friendly.’

But just because they looked better, loaded faster, and felt nicer to click on, did not mean they were delivering more appropriate information.

Likewise, someone could (and did) build an app to dispatch random volunteers to “rescue” people in need — and many people volunteered for such rescues. But should we have been encouraging random untrained and unaccountable volunteers to travel by boat (or, in one case I heard from someone in the field, by jetski) to try to rescue vulnerable people? The answer did not seem obvious to me.

Yet we lacked shared criteria with which we — as a community — could critically evaluate what we could do, in order to figure out what we really should do.

Re-aligning Responses Around Community-Centric Leadership

By the day before Hurricane Irma was projected to hit us, I was at my wits’ end — hardly sleeping, dropping balls, losing my temper. The network managed to stay together because of last-minute assistance from a handful of people who had experience facilitating network-enabled, community-centric crisis response. These organizers knew what problems to anticipate, and who knew how to cope with those problems. They helped us bring some order to the sprawling Irma Response network, established documentation for every project within it, and applied a framework to define each project’s objectives.

In the end, Irma swerved around South Florida and hit other parts of the state where we had less of a connection to the community; the main thing we did was help raise money to be distributed through a local foundation. Then things went back to normal all too fast. But the lessons stayed with me.

In the months and years afterward, I stayed in dialogue with that network of organizers.

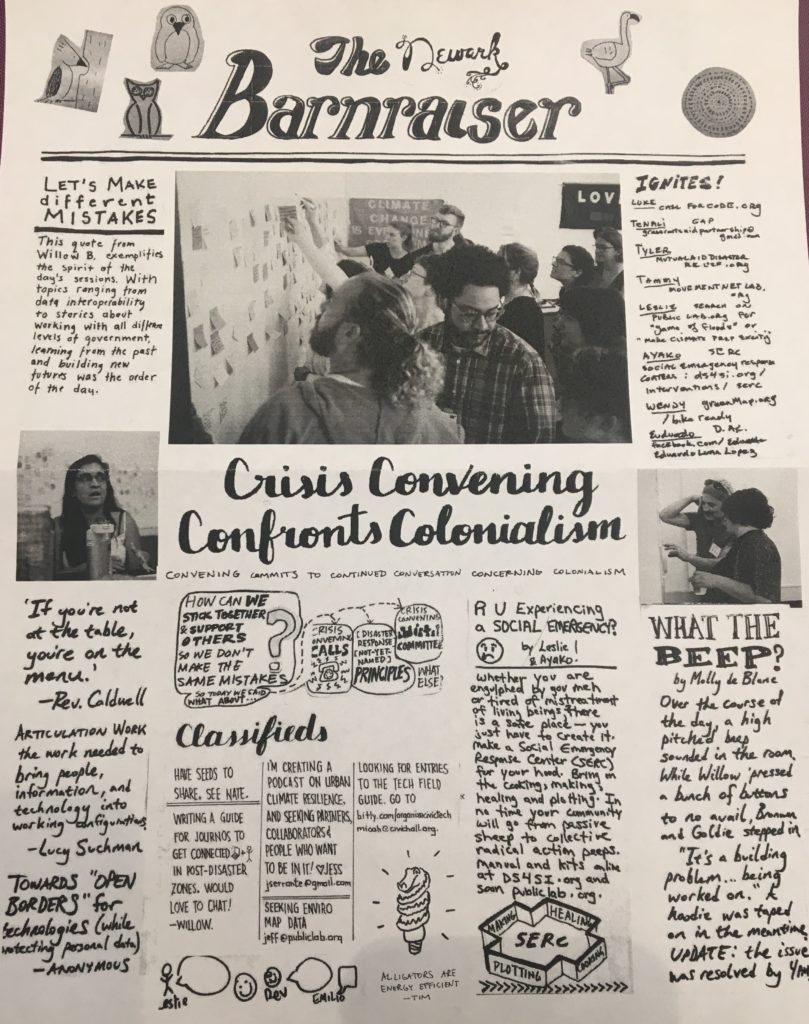

We convened a series of “Crisis Convenings” hosted by Public Laboratory, attended by organizers from Occupy Sandy, Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Katrina, among others. We shared stories of our own experiences, and found a range of commonalities. In between these events, we shared outputs with broader networks of organizers to solicit their feedback too.

Broadly, there were three themes that emerged through this process:

- The institutions tasked with responding to crisis tend to fail in their responsibilities to provide effective information, resources, and support — especially to communities that are not wealthy and powerful.

- The ad hoc networks of ‘digital humanitarians’ that emerge in response to any given publicized crisis tends to generate more light (visibility) than heat (impact) — and sometimes, their good intentions result in wasteful or even harmful mistakes.

- The most urgent, important, and potentially transformational leadership comes from impacted communities themselves, in which people with firsthand knowledge and longstanding relationships work together to solve their problems.

Across our network(s), the lessons were clear: the failures of formal institutional disaster responses (#1) and emergent ‘digital humanitarian’ disaster responses (#2) can best be corrected by re-aligning their power relationships to center community-based leadership (#3).

We agreed that these insights should be easier to share, so that — in the words of Willow Brugh — “we can at least make more interesting mistakes next time.”

So we reviewed existing statements of principles that had already informed our work or emerged from it. Personally, I’ve long aspired to uphold the principles of the Allied Media Projects and the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition. Some of us had helped articulate the principles of Occupy Sandy and Mutual Aid Disaster Relief. We also found Movement Generation’s Principles for a Just Transition, and thought hard about whether we really had anything new to offer. We listened deeply to organizers from Puerto Rico about how the botched response to Maria is inextricably tied up with a tragic history of colonialism and exploitation.

Ultimately we concluded that we could build upon this body of wisdom by offering a specific framework to guide those who might ask:

“What should we do NOW in this crisis?”

The resulting principles are designed to be immediately readable at a glance, yet one can unpack layers of insights within them and challenges among them:

1) Ask — and listen. We support those who most directly experience the impacts of crisis, and we act in response to their expressed needs.

2) Distribute Power. We promote strategies that effectively distribute information, resources, and decision-making ability, so that people can most effectively adapt to their local circumstances.

3) Collaborate Strategically. We work with institutions, to the extent that such work is in service of our goals of equity and justice.

4) Seek Appropriate Solutions. We understand that problem solving is an ongoing process requiring varied skills — and while we identify common patterns, every situation is unique.

5) Use Appropriate Technology. We prefer tools that are simple, accessible, freely usable, and well-documented.

Read here for some elaboration on each of these.

If people find this doc useful, I hope it evolves along with that use. Organizers can include it in manuals, and in community forums. You might use it to think through dilemmas that may emerge through your efforts. When there’s disagreement or concern, use it to guide your questions and your assessments.

Above all: this is a living document, and we’d welcome your feedback.

What happens now, when we’re all in crisis?

This crisis we’re in now isn’t the kind of thing any of us have had experience with, and I can’t even say those of us who drafted these principles had anything like it in mind. The COVID-19 pandemic is not local; it affects everyone. And it wasn’t quite sudden like a hurricane or earthquake; it unfolded over months, and it’s going to keep unfolding for a while.

So I don’t immediately know how these principles should apply here. Yet as I’ve watched countless “mutual aid” efforts and civic hacking projects popping up around the country and the world, and participated in a few myself, it’s clear that the principles are just as relevant as ever.

For example, Jen Pahlka — Code for America’s founder — recently called attention to a situation in which something is potentially more harmful than nothing:

Sometimes it takes some time, reflection, research and deliberation to figure out what should be done.

We do know that some people are far more vulnerable in this crisis than others. Those who want to do something should let this knowledge focus your attention.

Here’s how you can start: look for the people who have already been helping people who have already been in crisis. Such people are most likely to understand how the crisis is showing up and what kind of response is appropriate. Ask those helpers what they need; listen carefully. Try to build their capacity. Do so using appropriate technology. (New, unproven, and ‘black box’ technology is probably inappropriate. Default to simple, accessible, and when possible nonproprietary tools.) Know that the first answer that comes to mind might not be the most appropriate one. Work with institutions that are already working on the problem, to the extent that those institutions are working (or can be pressured to work) in effective and equitable ways. Repeat.

The root of the word “crisis,” as maytha alhassan once told me, means ‘turning point.’ A fork in the road. A pivotal moment like this can change the story we tell ourselves about our world. As if a veil has been lifted, we can see each other in a new light. As Rebecca Solnit writes in A Paradise Built In Hell, this is the light of people’s spirit, and it’s powerful stuff. It’s so vulnerable though; it’s easy to distort, and easy to snuff out.

We know that every crisis is unique, and also at the same time each crisis relates to and is shaped by a vast intersecting history of other crises. The communities that are most vulnerable to this virus — elders, uninsured, low-wage workers, etc — were already struggling with a failing healthcare system, a broken safety net, etc. Let’s use this as an opportunity to listen to those who’ve been experiencing these crises long before 2020. What’s their vision for a better future? Ask — and listen. Start with that.

I’m grateful to have had the chance to learn through this experience from so many leaders who brought these insights all together, especially Tammy Shapiro at Movement NetLab, Liz Barry at Public Lab, Emilio Velis at the Appropedia Foundation, and willowbl00 at large.

Humanism vs Human Services

Years ago, when I first began to consider the possibility of what would later become the Open Referral Initiative, I reached out to my former colleague Matt Siemer with a question.

When we’d worked together at Bread for the City, amid marathon Smiths playlists and recurring Werner Herzog impersonations, Matt had once expressed a strong distaste for the phrase “human services.” At the time I hadn’t really seen the problem. But when I suddenly found myself using the phrase with some regularity, something about it did feel off. I couldn’t put my finger on it (nor did I prefer “social services” for any clear reason). So I looped back to Matt, who had since gone off to study ‘hermeneutics,’ in what I imagined to be a remote stone tower so sky-high and constantly buttressed by clouds that one could simply drink from goblets suspended out of the window.

Matt’s response came all at once (via Facebook message) and left me sitting in silent awe for a while. It has lingered with me ever since, so I eventually asked Matt if I could share it here. Thanks to Matt for his permission, and generally for his weird and wonderful example of how to be a human being.

§

My trouble, if I’m remembering right, was not only with the words themselves (that they inadequately described the group of activities comprised therein), but that calling those tasks “human” services seemed an especially damning reflection of what we thought we were capable of as human beings.

Humanism was once the study of how best to understand each other. The thinking was that conflicts between human beings were largely the result of misinterpretations, and that by fostering a society rich in literature and the arts, people could use those narratives to connect their situations to those of other people and gain greater sympathy for the complexity of our shared condition. Compassion, community, mutual progress and peace were thought to be the logical end of efforts like universal education, public debate, and (above all) acknowledgement that we are all responsible for the welfare of each other. Humanism is often seen as the kernel leading to the enlightenment, democracy, social justice work, and public literacy campaigns. To be human under this rubric meant to strive toward the betterment of all, and to find in that striving a meaning for existing together. To be human meant to carry your part of the burden. I guess when I was younger I was guided by this definition of human, and as a result the idea of emergency assistance of different kinds being described as “human” services left a decidedly rank odor.

For, by contrast, what do we find under our so-named “human” services? The administration of various types of care for low-income people, almost always underfunded, taken on by some only because it hasn’t been appropriately assumed by all. And because there are so many in need and so few accepted models of assistance, too many fall through and the ones assisted are too rarely transformed by the intervention. And though they would like to do more, the few people interested in solving the issue of poverty are being forced to wait until the very last possible moment, when a person is homeless or horribly sick or hungry or mentally damaged, to offer help. What’s human about that—about neglecting widespread distress until it’s virtually unfixable and then handcuffing the people designated to help?

I don’t suppose you would blame me for objecting to labeling such services under a definition of human. Is it human to make hell on earth for other people? Is it human to ignore the basic needs of another body until they become so severe that the person can’t function in normal society? Is it human to have the vast majority of a people reify an economic structure based on the scarcity of currency and then blame the people who can’t access the scarce resource?

What we exhibit, we are. And what we do defines us. Human services are cruel, cowardly, resentful, and ungracious. They exist that way because they’re constructed not for the benefit of those who would like to help, but for those spiteful belligerents who don’t want to see assistance provided until someone is squirming on the ground begging for it. Under this model, solipsists can willfully ignore each other, buying trinkets with cotton paper that has value only because some have it and others don’t. And they will argue and fight to the point of hyperbole to make sure the human race isn’t acknowledged, understood, or cared for.

So call these services “human” if they’re human. But let’s also then define what human means: flawed, callous, meager, tardy, hard-hearted, inadequate, and lack-luster. Let’s call humans a race of sick souls eager to inflict sadness on each other, pitiless and ungracious animals not fit to exploit the gifts their forbearers passed on as the result of mutual labor. And if “human services” are the best effort that we can muster, if that’s the best we can do for each other, then let’s speak of humans as a black stain and keep blameless the minority that would rather work toward our extinction.

I suppose I would have said something to that effect. But that was six years ago when I was still thinking in terms of politics. It could be said now, perhaps more fairly, that the vast majority of people are unintentionally cruel when poverty is an abstraction, but when the reality of poverty reaches them on a visceral level, their reactions are surprising, emotional, compassionate, and occasionally inspired. Human services are as short-sighted and slapdash as any other human effort. They’re not perfect and they never will be. But they exist because a plurality of people still try to understand each other and still act when they meet an injustice. I can’t help but think of all the people whose lives have been completely changed by the Catholic Workers or the unions or Bread for the City or even the federal efforts like SCHIP or SNAP, and I have to acknowledge they have an impact, even if it isn’t nearly what we would all like it to be. In a way, it’s appropriate that efforts to save lives are considered “human” services. They may be the last vestige of a noble effort meant to teach us all how to be human.

— Matt Siemer

Helping Judy and her Son

Judith Hawkins’ family needs help, so please join me in supporting them in this time of crisis. See the crowdfunding page here, or just give in the gizmo below.

As is sadly typical, I’m coming to write about this a bit late, and it looks like the campaign is well on its way to meet its goal — but whatever, this goal is fit for passing. Let’s help Judy’s family heal.

Here’s some backstory for those who don’t have the privilege of knowing her:

While I was responsible for communications at Bread for the City, I was on the lookout for any media made by members of the communities we were serving. For the most part, the local blogs in Southeast D.C., for example, were written by newcomers who were championing the spirit of their neighborhoods. I knew and liked some of them, and learned a lot from reading their blogs, but also knew that they were generally telling stories that heralded the march of gentrification. Judy and her partner Valencia were two of the only voices I heard telling other stories — in their entirely self-produced mobile talk show, ‘It is What it Is’, which is often playful but also often looks directly at the sense of anger and adandonment and the attendant ills facing people who do not stand to benefit from the progress happening all around them.

It took a while but eventually I found the opportunity to recruit Judy to work on community media and mutual aid projects in the Bread for the City community. I count this as one of the biggest wins of my time there. Wherever she goes, Judy brings both a sharp critical eye and a whole lotta fun. From what little I’ve been able to see of her work in recent years, the ethic of mutual support she brings to Bread for the City southeast — from computer classes to media production to sewing circles — demonstrates an incredibly potent contrast between the dogged work of helping people solve problems on one hand while on the other offering them the time and space and confidence to learn new things and work together. (I think community organizations at their best should promote both, but have rarely seen it happen outside of Bread for the City.)

Fundraising-wise, I’m afraid it’s not super effective for me to be pondering the paradoxes inherent in the process of building solidarity across lines of race, class, etc. The struggle to bridge divergent cultures is real. (Judy made sure, for instance, that us kale-lovers took seriously the vital role of meat in community meals — yet she knows I will never fuck with those vienna sausages.) Even among those who would be allies, the interlocking mechanisms of power around us make it very difficult to engage in things that are pretty basic to building powerful relationships among us, such as speaking with candor. In my experience, those people who are motivated to try anyway are rare and vital. And yet even in those instances, all that ‘is what it is’ still very much is, claws ever out — chaos more readily erupting under foot, and with more cascading devastation.

We have an expanding ability to take actions like this, right here — to call for help beyond the block, across a world. It is one of the few reasons I have hope for the world. And yet beneath that hope, I yearn (and I hope you do too) for something quite different: a world where people’s security won’t hinge upon spontaneous appeals for individualized acts of kindness. That world may not be near to this one, but we can beckon for it. We can entice each other towards it.

Mid-Life Self-Evaluation: okay / sorry / not sorry

I’m turning 34, and reflecting on my path through the world so far. The work I’ve chosen is not getting easier, and one of the few things I miss about having actual jobs is the structure for constructive feedback from colleagues and superiors.

So I put together an evaluation survey (if you’re reading this, I figure you likely know me, so I hope you’ll take a moment to fill it out).

And I also conducted some self-evaluation. Specifically, I took stock of a number of instances in which I received positive or negative feedback, and analyzed it: Do I really consider this positive feedback to reflect a strength? Does this negative feedback carry an important signal? Or is it the kind of negative feedback that one should expect one way or another when engaging in creative disruption, just by nature of the undertaking?

People’s feedback often conveys as much or more about them as it does about you. And at the same time, strengths and weaknesses are weirdly interrelated. So to sort through my reflections, I tallied out in three columns — a kind of plus / delta / deal with it matrix. As I more continue to collect feedback from colleagues and friends, I’ll see what changes. Anyway, see below and let me know what I missed.

Drawing APIs: evolving our visual vocabulary

About a year ago, I posted over at the Sunlight Foundation’s blog about a facilitation tool with which I had been experimenting:

I find that it’s harder than it should be to have focused and effective conversations with non-technical people about open data, in large part because one of the key concepts involved is often described by an acronym (API), which itself abbreviates a phrase (‘application programming interface’) that is utterly ambiguous. This is the kind of problem that might only get worse when more words are thrown at it. …

So, I conducted an experiment at TransparencyCamp, and it turned out pretty well! The experiment was called “Draw An API,” and the instructions were:

- Someone describes what an API is.

- People draw what they think they’re hearing.

- Everyone discusses the results.

The results of this experiment were great! Continue Reading →

WITH AND OF AND BY AND FOR: on “Community as Platform”

In civic technology, community is the platform. How do we harness that power, and respect it?

[This essay was first published in Civic Quarterly #2, Winter 2014. Sharing here with fixed links, but without the fancy formatting and Livien Yin’s lovely illustrations.]

One of my favorite professors, Lawrence Goodwyn, used to say that as a historian his job was to study the continuity of error over time. The United States may have been founded upon the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal,” for example, but this has been historically untrue. Historically speaking, “all men are created equal” has meant “all white men who own land are created equal.” Everyone else—women, people of color, etc.—has had to fight for rights that were, at the time of our country’s founding, ostensibly inalienable.

Civic space is space in which citizens strive to reconcile an imperfect reality with their own social contract’s egalitarian promise. Civic space exists outside of both the market and the state; it is where citizens work together (or at least alongside each other) as peers, in public.

And yet I’ve seen the term “civic technology” applied to things like government data management systems, apps that provide easy access to public information and services, and even “the sharing economy” (i.e., apps that let people sell their services or rent their stuff to strangers). Such technologies very well might please their users and benefit everyone involved, but there’s nothing self-evidently civic about them.

Many define civic technology as that which enables people to build and wield power. I don’t disagree per se, but I do think this puts the cart before the horse. It’s kind of like defining public transportation as that which enables people to more efficiently get from A to B. Enabling people to wield power is what any technology does.

The whole point of civics is that people precede power. Civic technology, then, is that which helps citizens work together, particularly in the building of a world in which all people can live with dignity and respect. As civic designers, our job is to enable the correction of errors over time. Our functional specifications begin with statements like “all people should be treated as equals.”

Getting there, together

Tim O’Reilly’s “government as platform” manifesto lays out a vision of a 21st Century state. Drawing upon lessons learned from platforms like Windows and Facebook, Android and Apple, O’Reilly describes a lean government that sets policy, maintains infrastructure, monitors systems, exposes data—and otherwise hangs back until it’s needed to adjudicate.

Key pillars of his vision include:

- Embrace open standards;

- Design for participation;

- Lower the barriers to experimentation;

- Learn from your hackers;

- Develop a culture of measurement; and

- Build simple systems that can evolve.

It’s a grand vision—Jeffersonian, really. “[E]nable ‘We the People‘ to do most of the work,” wrote O’Reilly. Yet, in civics, our first task is usually to ask precisely who we mean when we say “We the people.” If, as a platform, the government’s primary role will be to manage a marketplace, who should we expect to exchange what, and with whom?

The idea that anybody can participate is the very source of government as platform’s value. It’s also a frequently revisited trope within the civic technology community, one that LaurenEllen McCann refers to as “The Myth of Everybody”. Because while anyone can participate, only some of us actually will.

For this reason, “government 2.0” poses as much of a threat to civics as it does an opportunity. This is not to say that government as platform is wrong; openness is a necessary precondition for civic politics. It’s just insufficient. If our systems are to be redesigned, whose interests are prioritized? Who gets to write on the whiteboards? …anybody?

The work of civic design begins precisely where the logic of government as platform ends, averting the many possible (yet not inevitable) tragedies that might befall the commons. In my work as a civic technologist, I’ve striven to apply a set of principles that I’ve come to call community as platform.

Community as Platform

At first glance, community as platform might seem like an awkward metaphor. Government is a self-contained system that literally produces data as its core operational function. It makes sense to build technology on top of it. Community, on the other hand, is inherently porous. It could exist among any set of people who interact with each other over time.

Yet a community’s health is determined by its members’ ability to share information and make effective decisions. This makes “platform thinking” a reasonably useful framework for our purpose. To construct the community as platform framework, we can start by remixing O’Reilly’s core principles of government as platform. Here:

- Embrace open standards becomes Establish your purpose;

- Design for participation becomes Design for diversity;

- Lower barriers to experimentation becomes Value participation;

- Learn from your hackers becomes Learn from each other;

- Develop a culture of measurement becomes Develop a culture of accountability; and

- Build simple systems becomes Navigate through complexity.

Establish your purpose

“Open by default” is government as a platform’s first principle. Take any framework for the science of community, however, and you‘ll likely find a different first principle (one potentially at odds with openness): set clear boundaries.

The value of a community emerges from its relationships, relationships predicated upon trust. Trust emerges from a shared sense of who we are and what is meaningful to us. This is, itself, a kind of boundary. Open communities define boundaries by establishing a shared sense of purpose, determining what is vs. is not allowed, what is good vs. what is bad, and what they ought to collaboratively do.

Since O’Reilly published his manifesto, civic technologists have produced a flurry of applications to help people find and use information to serve their interests and reshape their communities. In theory, anyone can use these apps, but we should anticipate that the mostly likely users will be those who are already digitally literate and well networked. The success of such apps might even amplify systemic patterns of resource allocation that benefit some communities while impoverishing others.

This is a dilemma. So are we gonna be all ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ or are we more like ಠ_ಠ? It depends on where we draw our lines; it depends on our purpose.

Design for Diversity

The world wide web flourished in large part due to its “choice architecture,” a design that nudged users to be “open by default.” Government as platform applies the same principles to public systems.

And yet because actually-existing civic society is structured by serious inequity and persistent disenfranchisement, we can expect that open by default will, by default, yield contributors who are whiter, more male, more heteronormative, and more likely to be employed by incorporated interests.

“Diverse by design” is community as platform’s corollary to open by default. By designing for diversity I don’t mean recruitment quotas or focus groups other aspirational gestures of inclusion; I mean designing systems that promote different kinds of leadership. At a tactical level, this entails adherence to the standard protocols of social and cultural interoperability, such as organizing events with childcare, transportation, translation services, gender-neutral bathrooms, etc.

At a strategic level, this entails structural interventions. Bill Traynor describes the value of “contrivances” that jump-start collaborative relationships between people who might not otherwise feel comfortable talking to each other. Contrivances could be anything from “icebreakers” to multi-stakeholder governance processes that gives decision-making weight to end users.

Code for Progress is an example of an organization that promotes diversity as its core function. Code for Progress recruits and trains people of color as programmers, then embeds them in community-based organizations. There, programmers prototype tools to meet the needs of their host organization and its community. Code for Progress isn’t open—not just anybody can join—but it’s terrifically civic.

Truly civic technology bypasses more than just technical or bureaucratic barriers; it engenders agency among those who would otherwise lack it.

Value participation

The notion that participation its own kind of reward can only get us so far. Without creative means of valuing participation, the civic hacking community will mostly consist of a disjointed mix of volunteers, professionals, entrepreneurs, and job-seekers. This is not to disparage any such people—you, dear reader, almost certainly fit at least one of these categories. But it wasn’t so long ago that the domain of civics was largely comprised of people who didn’t quite fit any of these molds.

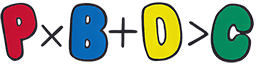

Here we should consider the “Calculus of Civic Engagement” that Anthea Watson Strong cites in her great essay “Three Levers of Civic Engagement”. Basically, whenever a citizen considers taking a civic action, they implicitly calculate the following formula:Where P is the probability that the action will affect an outcome, B is benefit to them of that outcome, D is the sense of civic duty derived from the action, and C is the cost of the action.

In English, a person will take a civic action if they estimate that the product of P (the probability that their action will affect an outcome) and B (their personal benefit of that outcome) plus D (their sense of civic duty) is greater than C (the cost of the action).

Watson-Strong suspects that most civic tech tools today chiefly aim to reduce the cost of action (C), or increase the probability of impact (P), but otherwise depend on sentiment (D). She urges us to remember, however, that civic technologists have an abnormally high sense of civic duty (D); most people are far more rational. In the end, civic politics cannot rely on our shared sense of civic duty.

I look at this equation and see B, the benefit of civic action, crying out for love. Civic politics should be chiefly concerned with the meeting of people’s needs; citizens‘ participation is invaluable, and such value should be made explicit in return. How might we do this?

The Smart Chicago Collaborative’s Civic User Testing Group organizes non-technical residents to test civic applications by paying for their time. Paying people for civic participation is not always the right thing to do; it tends to warp behavior and depress otherwise-intrinsic motivations. So we must find ways to meaningfully, non-monetarily value participants‘ time (e.g., mutual credit systems, like community timebanks, in which participants earn credit for activities like mentoring and tech support).

Ultimately, a community should offer more than warm fuzzies to participants. It should offer tangible benefits.

Learn from each other

Government as platform encourages users to do unexpected, possibly unprecedented things. In the words of government 2.0, we “learn from our hackers.”

Likewise, a healthy community learns from its margins—but not just its savviest, most successful members. A healthy community also learns from members who struggle the most. They have firsthand knowledge of what’s not working; in some cases, they may have even devised their own solutions to the problems. From the mainstream of a community, such perspectives can often be hard to see or hear.

Truly transformative civic technology promotes the agency of a community’s most marginalized members. The greatest potential for civic innovation exists when those who experience a problem and those who have technical skills interact with one another. Zaid Hassan’s “social labs,” for example, convene people from different levels of a dysfunctional system—from the ground to the executive, from policymakers to academics—to collaboratively prototype experimental solutions to complex problems.

Consider how we might apply this principle to the processes of working together. What if we replaced Agile development’s “product owners” with “problem owners?” What would happen if we transferred the critical levers of production—the ability to generate user stores, prioritize backlogs, and evaluate output—directly in the hands of those who authentically represent the interests of their community? I suspect this process would yield relatively few new products; rather, it would likely uncover new, transformative ways of working with entirely boring technology.

Foster a culture of accountability

What counts? What’s it worth? What works? How do we know? Civic technology should help people ask questions, share what they discover, and hold those in positions of responsibility accountable for the design and evolution of systems that serve our interests.

Again, lean methodology is a useful point of reference, as it’s premised on a cycle of learning: Do something, observe what happened, and analyze it, iteratively, together. The same process guides effective public work; but it’s that “together” part which ought to be considered the defining aspect of the process and/or its products.

Remember that a lean company learns by extracting data from tests conducted on users. Those learnings are channeled into product. A community, however, learns when its members communicate with each other in public, and channel those learnings back into shared, collective knowledge.

At a minimum, a culture of accountability would entail that civic design’s priorities, processes and outcomes are transparent to everyone—not just the institutions that fund development or purchase product. At its fullest expression, civic technology would create feedback loops between institutions and community members that enable new forms (or revive older forms) of institutional governance, such as cooperatives and other dues-paying membership bodies, election of non-profit leadership, participatory budgeting, and so on.[See also, my chapter in Code for America’s “Beyond Transparency:” “Toward a Community Data Commons.”[/ref]

This principle requires us to answer some urgent questions: If society is increasingly subject to “algorithmic regulation”—another O’Reilly notion—then who writes the algorithms? Who determines what is measured, and what will trigger interventions? Who decides what’s done with metadata? Civic technology should enable the public remediation of algorithmic regulation; otherwise, the whole prospect is frankly terrifying.

Navigate through complexity

Simplicity is a virtue. Reality is complex.

The complexity of social systems can mask the reality that what’s efficient for institutions (even civic institutions) isn’t always effective for individual people—and vice versa. When developing products, it’s all too easy to aim for simple and end up at simplistic, i.e., with an output that may work superficially yet fail to address the systemic nature of its problem. Such superficial fixes tend to eventually become part of the problems themselves.

Those of us seeking solutions must strive for simplicity while designing for complexity. We must bring people on this journey with us.

One expression of this principle is a prerogative to visualize abstract technical systems, so that non-technical people can understand their essential workings at a glance.

A great example of this is “Every Network Tells A Story” a tool produced by the Open Technology Institute to aid in the building of community wireless networks. Through simple icons for different kinds of routers and signals, “Every Network Tells a Story” enables anyone to grasp the basics of wireless technology. Then, with only scissors and tape (actual maps are optional), the toolkit prompts participants to visualize their neighborhood’s social topography, and layer their desired communications infrastructure on top of it.

Inspired by this approach, the Open Referral Initiative is experimenting with a similar kind of participatory iconography for databases, records, APIs, and so forth. Relatedly, I think the Noun Project could turn out to be one of the most essential civic technologies of our future.

Towards truly civic technology

Establish a clear purpose; design for diversity; value participation; learn from each other; foster a culture of accountability; and navigate through complexity. These are the principles that I aspire to practice in my own work as a civic technologist.

Only occasionally do I feel like we‘re getting it right. But those moments are like magic: something emerges that is greater than the sum of each individual’s perspective, the invisible becomes visible, and you can sense the world of possibilities expand.