Facing the crisis of insurance in Miami and beyond: polycentric strategies for a risky world

Tl;dr– Check out the report on the 2024 Miami Dade Property Insurance Strategy Forum, now available on Insurance for Good. In this post, I’ll tell the story of how the strategy forum happened in the first place, and share my own takeaways from it.

When people learn that I’m from Miami, they sometimes ask me how long we have until it’s under water. I always respond that long before it’s actually flooded, the real estate market will sink under the collapsing insurance market (and with it, perhaps our entire economy). I’m not just a lone Cassandra here; at least some people well-established in the real estate and insurance sectors have been warning us about this for years. We’re already seeing this future intrude into our present: premiums in South Florida are climbing in many cases about 20% a year – and given the damage from Helene and Milton, we can expect that climb to accelerate next year. At this pace, most people simply won’t be able to afford insurance here within the next decade. So even if our decades-long lucky hurricane-miss streak holds, we’re already well on our way to being in over our heads.

Talking about this stuff doesn’t exactly make me popular in Miami’s social scene. It’s hard to imagine a culture less suited for this kind of foresight than our fast-fashioned, pleasure-centered, disposable Magic City. But there are at least a couple dozen other people out here thinking about our actual future, and it hasn’t been hard for us to find each other. A significant fraction of that tiny subculture participates in a book club about climate change and Miami that I have helped facilitate for years. (We started in 2020 with the publication of Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine Wilkerson’s All We Can Save; and we just last month finished the good Dr Johnson’s second book, What If We Get It Right?, an excellent and let’s just say poignant post-election read.)

One of our book club’s longstanding members is Kate Stein, who was a local journalist covering climate issues when I first met her while attending some (bleak!) City of Miami “sea level rise commission” meetings. Kate later served as the city of Surfside’s first sustainability and resilience officer, right around the time of the terrible condo collapse there. From these harrowing experiences, Kate followed her nose into graduate studies in risk management at the London School of Economics – and now works at WTW, one of the global insurance brokerages headquartered in London.

Last year I was visiting London and caught up with Kate over breakfast at Dishoom. It wasn’t long before I expressed some cynicism about the state of the insurance market, to which Kate responded with her characteristic optimism. “There are things we can do,” Kate insisted to me. She believes that there are various ways that governments, insurance companies, real estate developers, and other institutions could be working together to facilitate adaptation and risk management more effectively. “We just don’t have any opportunities to get together and talk to each other.”

Well that, I said, is something I can help with.

Continue Reading →Something is not necessarily better than nothing: Introducing the Principles of Equitable Disaster Response

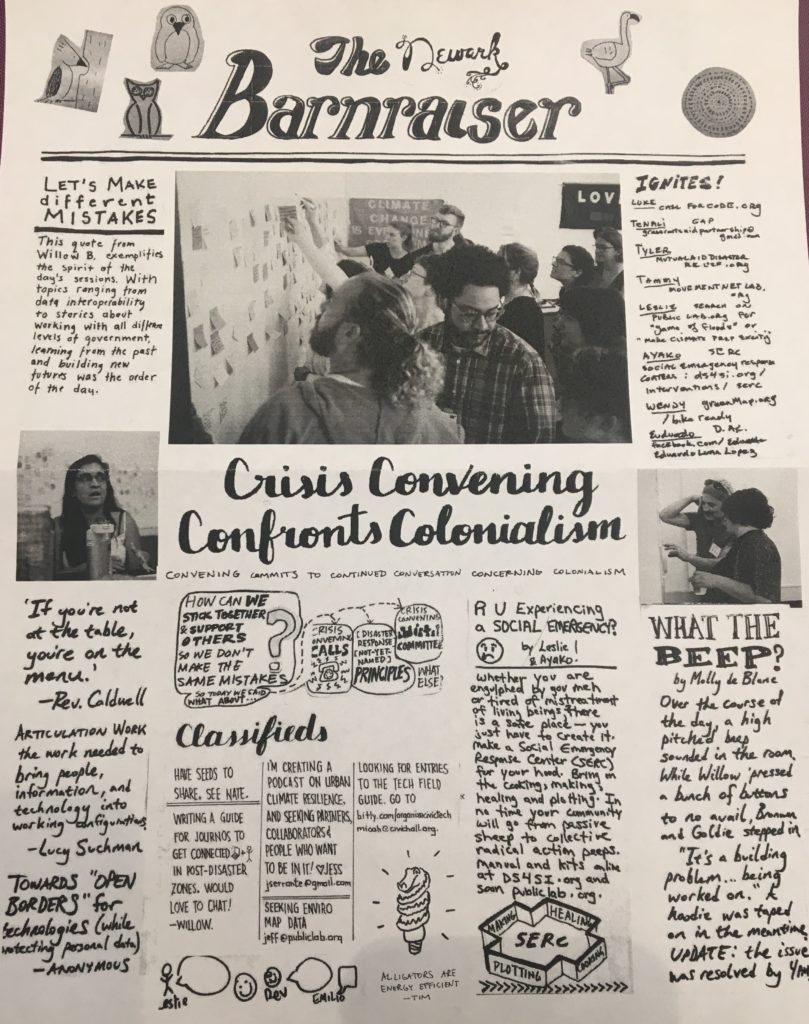

Last week, a distributed team of community organizers published the Principles of Equitable and Effective Disaster Response. This is a document that we’ve developed through a series of in-person convenings and distributed rounds of feedback over the past two years. (You can review and comment upon the original draft here.)

We first articulated these principles with natural disasters in mind, but now – with a pandemic emergency upon us – we’re sharing them in hopes that they may be useful for people and communities that are mobilizing to respond to this new global crisis.

Below I’ll share some backstory on how I came to be involved in producing this document, and why I think it matters.

Hard Lessons from Hurricane Irma

During the week before Hurricane Irma in 2017, I started up the Irma Response slack which quickly grew into a virtual network of about a thousand ‘digital crisis responders.’ As a network, we did some things that I’m proud of.

In the end, the storm swerved past Miami-Dade. The disaster never quite happened (to us, anyway). Nevertheless, this experience was sobering for me.

First and foremost, I saw firsthand how our institutional systems were almost universally ill-prepared to respond to this crisis. From governments to nonprofits, it was bleak: poor plans, poorly coordinated and poorly communicated. (The number of shelters were woefully insufficient; the evacuation order came late and left tens of thousands jammed on roads as the hurricane approached; the government and the Red Cross blamed each other. I never did find out what the Florida VOAD — Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster — was supposed to be doing, let alone what it actually did. Etc.)

I also saw how readily regular people from all over the country and the world rallied to help online. This swarm of support was initially exhilarating, then eventually exhausting and frustrating. I saw alarming gaps between these digital responders’ good intentions, their ideas, and the reality of what people needed on the ground.

Most importantly, I saw how the most urgent and appropriate responses to the situation came directly from communities that were most vulnerable to this crisis. Local leaders like Vee Gunder were the first to respond in the communities, with the clearest line of sight to what was needed, and the strongest connection to the people in need — and they would still be there working after the attention withered away. Amid all the attention paid to either the mistakes of the formal institutions, and to the flashy websites and data visualizations produced by the network of civic hackers, these voices were the most important — yet the hardest to hear.

The Crises of Network-Centric Crisis Response

Since I started the Irma Response network, I felt some responsibility for the things happening in it.

In the week before the storm was projected to hit, I found myself spending 18+ hour days tending to the network. An enervating portion of that time entailed responding to crises that were precipitated by our own crisis responses. I intervened when I found people putting out information that could put vulnerable Florida residents (like undocumented residents or disabled people) in danger. I interjected when I found people hacking on “first thought best thought” applications that — if they’d ever be used at all — would waste a lot of time and energy, and maybe even make a messy situation worse. I spent hours a day asking why people were doing various things, and asking people to reconsider whether those things really ought to be done.

The most common response I got was: “well we have to do something!” And I’d have to point out that this was not actually true.

These were difficult conversations. Everyone involved had the best of intentions. They were volunteering their time, out of care for people in danger. They did not feel like there was time to waste in “philosophical discussions,” and they did not feel like we should be “political.”

And at a glance one could understand where they were coming from: with no money and a matter of days, our network built websites, and generated data visualizations, that looked way better than those produced by government agencies and giant organizations with multi-million dollar budgets and timescales of years. Our digital products loaded faster. They were ‘user friendly.’

But just because they looked better, loaded faster, and felt nicer to click on, did not mean they were delivering more appropriate information.

Likewise, someone could (and did) build an app to dispatch random volunteers to “rescue” people in need — and many people volunteered for such rescues. But should we have been encouraging random untrained and unaccountable volunteers to travel by boat (or, in one case I heard from someone in the field, by jetski) to try to rescue vulnerable people? The answer did not seem obvious to me.

Yet we lacked shared criteria with which we — as a community — could critically evaluate what we could do, in order to figure out what we really should do.

Re-aligning Responses Around Community-Centric Leadership

By the day before Hurricane Irma was projected to hit us, I was at my wits’ end — hardly sleeping, dropping balls, losing my temper. The network managed to stay together because of last-minute assistance from a handful of people who had experience facilitating network-enabled, community-centric crisis response. These organizers knew what problems to anticipate, and who knew how to cope with those problems. They helped us bring some order to the sprawling Irma Response network, established documentation for every project within it, and applied a framework to define each project’s objectives.

In the end, Irma swerved around South Florida and hit other parts of the state where we had less of a connection to the community; the main thing we did was help raise money to be distributed through a local foundation. Then things went back to normal all too fast. But the lessons stayed with me.

In the months and years afterward, I stayed in dialogue with that network of organizers.

We convened a series of “Crisis Convenings” hosted by Public Laboratory, attended by organizers from Occupy Sandy, Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Katrina, among others. We shared stories of our own experiences, and found a range of commonalities. In between these events, we shared outputs with broader networks of organizers to solicit their feedback too.

Broadly, there were three themes that emerged through this process:

- The institutions tasked with responding to crisis tend to fail in their responsibilities to provide effective information, resources, and support — especially to communities that are not wealthy and powerful.

- The ad hoc networks of ‘digital humanitarians’ that emerge in response to any given publicized crisis tends to generate more light (visibility) than heat (impact) — and sometimes, their good intentions result in wasteful or even harmful mistakes.

- The most urgent, important, and potentially transformational leadership comes from impacted communities themselves, in which people with firsthand knowledge and longstanding relationships work together to solve their problems.

Across our network(s), the lessons were clear: the failures of formal institutional disaster responses (#1) and emergent ‘digital humanitarian’ disaster responses (#2) can best be corrected by re-aligning their power relationships to center community-based leadership (#3).

We agreed that these insights should be easier to share, so that — in the words of Willow Brugh — “we can at least make more interesting mistakes next time.”

So we reviewed existing statements of principles that had already informed our work or emerged from it. Personally, I’ve long aspired to uphold the principles of the Allied Media Projects and the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition. Some of us had helped articulate the principles of Occupy Sandy and Mutual Aid Disaster Relief. We also found Movement Generation’s Principles for a Just Transition, and thought hard about whether we really had anything new to offer. We listened deeply to organizers from Puerto Rico about how the botched response to Maria is inextricably tied up with a tragic history of colonialism and exploitation.

Ultimately we concluded that we could build upon this body of wisdom by offering a specific framework to guide those who might ask:

“What should we do NOW in this crisis?”

The resulting principles are designed to be immediately readable at a glance, yet one can unpack layers of insights within them and challenges among them:

1) Ask — and listen. We support those who most directly experience the impacts of crisis, and we act in response to their expressed needs.

2) Distribute Power. We promote strategies that effectively distribute information, resources, and decision-making ability, so that people can most effectively adapt to their local circumstances.

3) Collaborate Strategically. We work with institutions, to the extent that such work is in service of our goals of equity and justice.

4) Seek Appropriate Solutions. We understand that problem solving is an ongoing process requiring varied skills — and while we identify common patterns, every situation is unique.

5) Use Appropriate Technology. We prefer tools that are simple, accessible, freely usable, and well-documented.

Read here for some elaboration on each of these.

If people find this doc useful, I hope it evolves along with that use. Organizers can include it in manuals, and in community forums. You might use it to think through dilemmas that may emerge through your efforts. When there’s disagreement or concern, use it to guide your questions and your assessments.

Above all: this is a living document, and we’d welcome your feedback.

What happens now, when we’re all in crisis?

This crisis we’re in now isn’t the kind of thing any of us have had experience with, and I can’t even say those of us who drafted these principles had anything like it in mind. The COVID-19 pandemic is not local; it affects everyone. And it wasn’t quite sudden like a hurricane or earthquake; it unfolded over months, and it’s going to keep unfolding for a while.

So I don’t immediately know how these principles should apply here. Yet as I’ve watched countless “mutual aid” efforts and civic hacking projects popping up around the country and the world, and participated in a few myself, it’s clear that the principles are just as relevant as ever.

For example, Jen Pahlka — Code for America’s founder — recently called attention to a situation in which something is potentially more harmful than nothing:

Sometimes it takes some time, reflection, research and deliberation to figure out what should be done.

We do know that some people are far more vulnerable in this crisis than others. Those who want to do something should let this knowledge focus your attention.

Here’s how you can start: look for the people who have already been helping people who have already been in crisis. Such people are most likely to understand how the crisis is showing up and what kind of response is appropriate. Ask those helpers what they need; listen carefully. Try to build their capacity. Do so using appropriate technology. (New, unproven, and ‘black box’ technology is probably inappropriate. Default to simple, accessible, and when possible nonproprietary tools.) Know that the first answer that comes to mind might not be the most appropriate one. Work with institutions that are already working on the problem, to the extent that those institutions are working (or can be pressured to work) in effective and equitable ways. Repeat.

The root of the word “crisis,” as maytha alhassan once told me, means ‘turning point.’ A fork in the road. A pivotal moment like this can change the story we tell ourselves about our world. As if a veil has been lifted, we can see each other in a new light. As Rebecca Solnit writes in A Paradise Built In Hell, this is the light of people’s spirit, and it’s powerful stuff. It’s so vulnerable though; it’s easy to distort, and easy to snuff out.

We know that every crisis is unique, and also at the same time each crisis relates to and is shaped by a vast intersecting history of other crises. The communities that are most vulnerable to this virus — elders, uninsured, low-wage workers, etc — were already struggling with a failing healthcare system, a broken safety net, etc. Let’s use this as an opportunity to listen to those who’ve been experiencing these crises long before 2020. What’s their vision for a better future? Ask — and listen. Start with that.

I’m grateful to have had the chance to learn through this experience from so many leaders who brought these insights all together, especially Tammy Shapiro at Movement NetLab, Liz Barry at Public Lab, Emilio Velis at the Appropedia Foundation, and willowbl00 at large.

Humanism vs Human Services

Years ago, when I first began to consider the possibility of what would later become the Open Referral Initiative, I reached out to my former colleague Matt Siemer with a question.

When we’d worked together at Bread for the City, amid marathon Smiths playlists and recurring Werner Herzog impersonations, Matt had once expressed a strong distaste for the phrase “human services.” At the time I hadn’t really seen the problem. But when I suddenly found myself using the phrase with some regularity, something about it did feel off. I couldn’t put my finger on it (nor did I prefer “social services” for any clear reason). So I looped back to Matt, who had since gone off to study ‘hermeneutics,’ in what I imagined to be a remote stone tower so sky-high and constantly buttressed by clouds that one could simply drink from goblets suspended out of the window.

Matt’s response came all at once (via Facebook message) and left me sitting in silent awe for a while. It has lingered with me ever since, so I eventually asked Matt if I could share it here. Thanks to Matt for his permission, and generally for his weird and wonderful example of how to be a human being.

§

My trouble, if I’m remembering right, was not only with the words themselves (that they inadequately described the group of activities comprised therein), but that calling those tasks “human” services seemed an especially damning reflection of what we thought we were capable of as human beings.

Humanism was once the study of how best to understand each other. The thinking was that conflicts between human beings were largely the result of misinterpretations, and that by fostering a society rich in literature and the arts, people could use those narratives to connect their situations to those of other people and gain greater sympathy for the complexity of our shared condition. Compassion, community, mutual progress and peace were thought to be the logical end of efforts like universal education, public debate, and (above all) acknowledgement that we are all responsible for the welfare of each other. Humanism is often seen as the kernel leading to the enlightenment, democracy, social justice work, and public literacy campaigns. To be human under this rubric meant to strive toward the betterment of all, and to find in that striving a meaning for existing together. To be human meant to carry your part of the burden. I guess when I was younger I was guided by this definition of human, and as a result the idea of emergency assistance of different kinds being described as “human” services left a decidedly rank odor.

For, by contrast, what do we find under our so-named “human” services? The administration of various types of care for low-income people, almost always underfunded, taken on by some only because it hasn’t been appropriately assumed by all. And because there are so many in need and so few accepted models of assistance, too many fall through and the ones assisted are too rarely transformed by the intervention. And though they would like to do more, the few people interested in solving the issue of poverty are being forced to wait until the very last possible moment, when a person is homeless or horribly sick or hungry or mentally damaged, to offer help. What’s human about that—about neglecting widespread distress until it’s virtually unfixable and then handcuffing the people designated to help?

I don’t suppose you would blame me for objecting to labeling such services under a definition of human. Is it human to make hell on earth for other people? Is it human to ignore the basic needs of another body until they become so severe that the person can’t function in normal society? Is it human to have the vast majority of a people reify an economic structure based on the scarcity of currency and then blame the people who can’t access the scarce resource?

What we exhibit, we are. And what we do defines us. Human services are cruel, cowardly, resentful, and ungracious. They exist that way because they’re constructed not for the benefit of those who would like to help, but for those spiteful belligerents who don’t want to see assistance provided until someone is squirming on the ground begging for it. Under this model, solipsists can willfully ignore each other, buying trinkets with cotton paper that has value only because some have it and others don’t. And they will argue and fight to the point of hyperbole to make sure the human race isn’t acknowledged, understood, or cared for.

So call these services “human” if they’re human. But let’s also then define what human means: flawed, callous, meager, tardy, hard-hearted, inadequate, and lack-luster. Let’s call humans a race of sick souls eager to inflict sadness on each other, pitiless and ungracious animals not fit to exploit the gifts their forbearers passed on as the result of mutual labor. And if “human services” are the best effort that we can muster, if that’s the best we can do for each other, then let’s speak of humans as a black stain and keep blameless the minority that would rather work toward our extinction.

I suppose I would have said something to that effect. But that was six years ago when I was still thinking in terms of politics. It could be said now, perhaps more fairly, that the vast majority of people are unintentionally cruel when poverty is an abstraction, but when the reality of poverty reaches them on a visceral level, their reactions are surprising, emotional, compassionate, and occasionally inspired. Human services are as short-sighted and slapdash as any other human effort. They’re not perfect and they never will be. But they exist because a plurality of people still try to understand each other and still act when they meet an injustice. I can’t help but think of all the people whose lives have been completely changed by the Catholic Workers or the unions or Bread for the City or even the federal efforts like SCHIP or SNAP, and I have to acknowledge they have an impact, even if it isn’t nearly what we would all like it to be. In a way, it’s appropriate that efforts to save lives are considered “human” services. They may be the last vestige of a noble effort meant to teach us all how to be human.

— Matt Siemer

Helping Judy and her Son

Judith Hawkins’ family needs help, so please join me in supporting them in this time of crisis. See the crowdfunding page here, or just give in the gizmo below.

As is sadly typical, I’m coming to write about this a bit late, and it looks like the campaign is well on its way to meet its goal — but whatever, this goal is fit for passing. Let’s help Judy’s family heal.

Here’s some backstory for those who don’t have the privilege of knowing her:

While I was responsible for communications at Bread for the City, I was on the lookout for any media made by members of the communities we were serving. For the most part, the local blogs in Southeast D.C., for example, were written by newcomers who were championing the spirit of their neighborhoods. I knew and liked some of them, and learned a lot from reading their blogs, but also knew that they were generally telling stories that heralded the march of gentrification. Judy and her partner Valencia were two of the only voices I heard telling other stories — in their entirely self-produced mobile talk show, ‘It is What it Is’, which is often playful but also often looks directly at the sense of anger and adandonment and the attendant ills facing people who do not stand to benefit from the progress happening all around them.

It took a while but eventually I found the opportunity to recruit Judy to work on community media and mutual aid projects in the Bread for the City community. I count this as one of the biggest wins of my time there. Wherever she goes, Judy brings both a sharp critical eye and a whole lotta fun. From what little I’ve been able to see of her work in recent years, the ethic of mutual support she brings to Bread for the City southeast — from computer classes to media production to sewing circles — demonstrates an incredibly potent contrast between the dogged work of helping people solve problems on one hand while on the other offering them the time and space and confidence to learn new things and work together. (I think community organizations at their best should promote both, but have rarely seen it happen outside of Bread for the City.)

Fundraising-wise, I’m afraid it’s not super effective for me to be pondering the paradoxes inherent in the process of building solidarity across lines of race, class, etc. The struggle to bridge divergent cultures is real. (Judy made sure, for instance, that us kale-lovers took seriously the vital role of meat in community meals — yet she knows I will never fuck with those vienna sausages.) Even among those who would be allies, the interlocking mechanisms of power around us make it very difficult to engage in things that are pretty basic to building powerful relationships among us, such as speaking with candor. In my experience, those people who are motivated to try anyway are rare and vital. And yet even in those instances, all that ‘is what it is’ still very much is, claws ever out — chaos more readily erupting under foot, and with more cascading devastation.

We have an expanding ability to take actions like this, right here — to call for help beyond the block, across a world. It is one of the few reasons I have hope for the world. And yet beneath that hope, I yearn (and I hope you do too) for something quite different: a world where people’s security won’t hinge upon spontaneous appeals for individualized acts of kindness. That world may not be near to this one, but we can beckon for it. We can entice each other towards it.

Mid-Life Self-Evaluation: okay / sorry / not sorry

I’m turning 34, and reflecting on my path through the world so far. The work I’ve chosen is not getting easier, and one of the few things I miss about having actual jobs is the structure for constructive feedback from colleagues and superiors.

So I put together an evaluation survey (if you’re reading this, I figure you likely know me, so I hope you’ll take a moment to fill it out).

And I also conducted some self-evaluation. Specifically, I took stock of a number of instances in which I received positive or negative feedback, and analyzed it: Do I really consider this positive feedback to reflect a strength? Does this negative feedback carry an important signal? Or is it the kind of negative feedback that one should expect one way or another when engaging in creative disruption, just by nature of the undertaking?

People’s feedback often conveys as much or more about them as it does about you. And at the same time, strengths and weaknesses are weirdly interrelated. So to sort through my reflections, I tallied out in three columns — a kind of plus / delta / deal with it matrix. As I more continue to collect feedback from colleagues and friends, I’ll see what changes. Anyway, see below and let me know what I missed.

Drawing APIs: evolving our visual vocabulary

About a year ago, I posted over at the Sunlight Foundation’s blog about a facilitation tool with which I had been experimenting:

I find that it’s harder than it should be to have focused and effective conversations with non-technical people about open data, in large part because one of the key concepts involved is often described by an acronym (API), which itself abbreviates a phrase (‘application programming interface’) that is utterly ambiguous. This is the kind of problem that might only get worse when more words are thrown at it. …

So, I conducted an experiment at TransparencyCamp, and it turned out pretty well! The experiment was called “Draw An API,” and the instructions were:

- Someone describes what an API is.

- People draw what they think they’re hearing.

- Everyone discusses the results.

The results of this experiment were great! Continue Reading →